- Out of United States

- Posts

- The Shadow of Authoritarianism

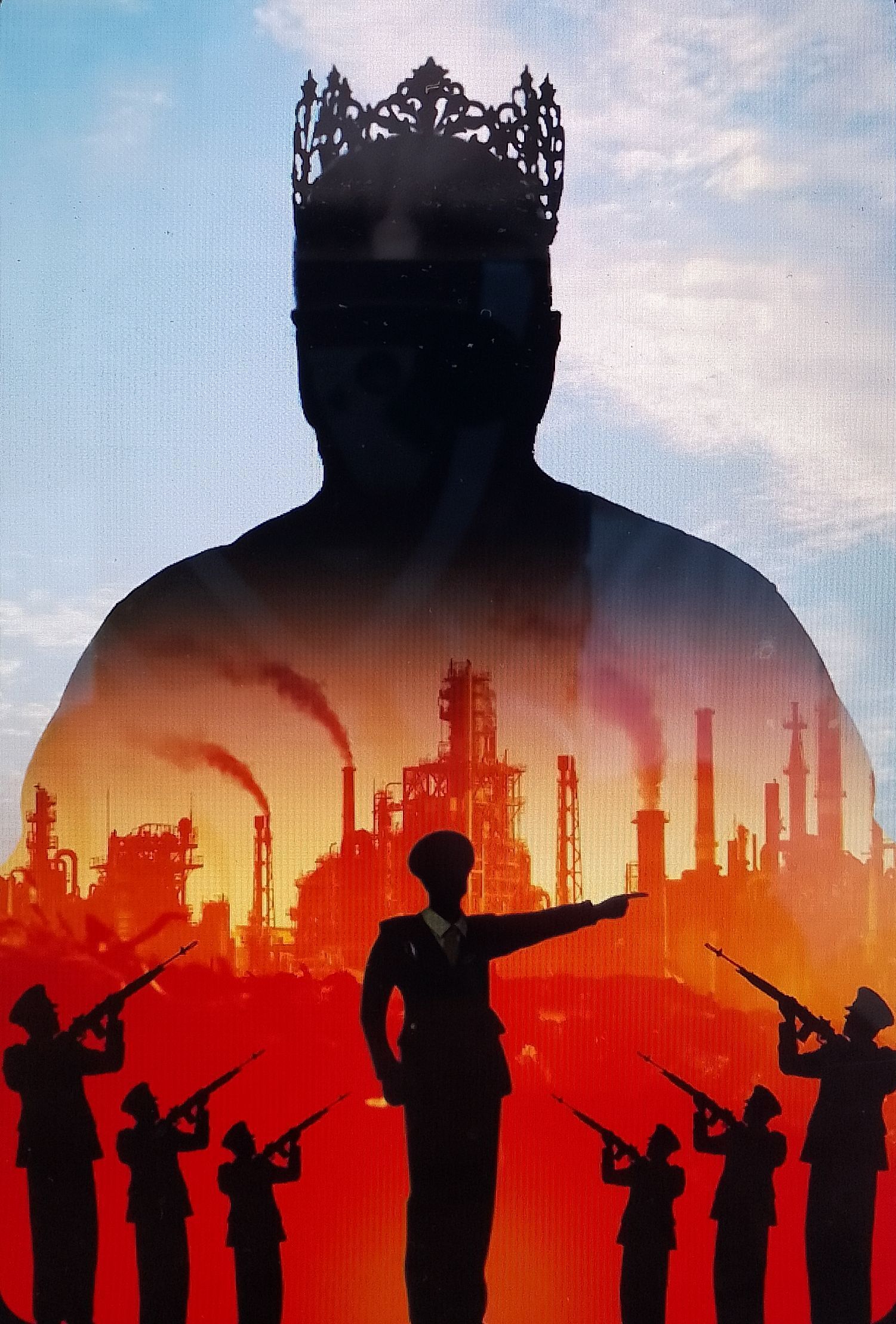

The Shadow of Authoritarianism

A Jungian Perspective on "Mourn, or Else" and a Path to Health

In Tressie McMillan Cottom’s incisive New York Times opinion piece, "Mourn, or Else," the assassination of conservative figure Charlie Kirk serves as a lens through which to examine the consolidation of state, corporate, and media power under an authoritarian administration led by President Trump. Drawing on Carl Jung’s psychological framework, particularly his concepts of the collective shadow, individuation, and the archetypes that shape societal behavior, this essay explores how Cottom’s critique reveals a society grappling with its unacknowledged shadow, manipulated by authoritarian forces to suppress dissent and erode democratic principles. Combined with insights from related critiques, such as those by Thom Hartmann and Bandy X. Lee, this analysis situates the current political crisis within a Jungian understanding of collective psyche, offering pathways toward resilience and resistance through psychological awareness.

Cottom’s narrative begins with the viral spread of Kirk’s assassination video, a phenomenon that reflects what Jung might describe as the collective shadow erupting into public consciousness. The shadow, in Jungian terms, represents the repressed, unacknowledged aspects of the psyche—both individual and collective—that manifest in destructive behaviors when ignored. The public’s fascination with the video and the subsequent orchestrated mourning, driven by a unified media narrative, suggest a society projecting its fears and divisions onto a single event. Cottom notes the shift from “If it bleeds, it leads” to “monetize misery,” a dynamic that exploits the collective shadow’s attraction to chaos and spectacle. Jung would argue that this obsession with sensationalized violence reveals a society disconnected from its deeper values, manipulated by external forces—here, an authoritarian administration and its corporate allies—to amplify division and fear.

The administration’s response, as Cottom details, mirrors historical authoritarian tactics, such as those during the Red Scare or Nazi Germany, where dissent was criminalized. Thom Hartmann’s comparison of FCC Chairman Brendan Carr’s threats against Disney/ABC to Goebbels’ censorship of comedians in 1939 underscores this parallel. From a Jungian perspective, this suppression reflects the archetype of the Tyrant, a shadow manifestation of the King archetype, which seeks order through control rather than wisdom. The Tyrant archetype, embodied in Trump’s demands to silence critics like Jimmy Kimmel or Stephen Colbert, thrives on projecting its insecurities onto perceived enemies, labeling dissent as “illegal” or “anti-American.” Hartmann’s reference to Trump’s claim that critical news stories are “illegal” illustrates this projection, where the Tyrant seeks to eliminate any mirror that reflects its flaws.

Cottom’s critique of media consolidation, particularly the Ellison family’s growing control over outlets like Paramount and potentially TikTok, highlights how corporate power amplifies this authoritarian agenda. Jung’s concept of the collective unconscious suggests that societal narratives, shaped by archetypes, influence behavior on a mass scale. When media conglomerates align with the Tyrant archetype, they manipulate the collective unconscious, replacing diverse narratives with a singular, partisan story. This consolidation, as Cottom warns, threatens First Amendment rights and distorts reality, creating a psychic environment where individuals feel compelled to self-censor. The doxxing of citizens who fail to mourn Kirk “appropriately” and the deployment of bot armies to stoke division, as Cottom describes, reflect a deliberate strategy to fragment the collective psyche, preventing the integration necessary for a healthy democracy.

Hartmann’s analysis of the “radical left violence” narrative as a “Big Lie” further illuminates this manipulation. Jung would see this as a projection of the collective shadow onto a scapegoated “other”—in this case, a fabricated “radical left.” By framing political violence, such as the Michigan church shooting, as “anti-Christian” rather than examining its roots in right-wing radicalization, the administration avoids confronting its own shadow. This tactic, reminiscent of Hitler’s propaganda strategies as Hartmann notes, relies on repetition to make falsehoods credible, exploiting the collective unconscious’s susceptibility to archetypal fears of chaos and betrayal. The absence of a significant “radical left” in modern America, as Hartmann argues, underscores the constructed nature of this narrative, designed to justify censorship and militarization.

Cottom’s critique of the myth of civil debate as a democratic cornerstone resonates with Jung’s emphasis on confronting the shadow rather than idealizing rational discourse. She notes that figures like Kirk, products of a well-funded conservative machine, used performative debate to provoke rather than engage, a strategy Jung might interpret as the Trickster archetype at work. The Trickster, while potentially transformative, becomes destructive when co-opted by the Tyrant, sowing chaos to undermine trust. Cottom’s reference to Steve Bannon’s “muzzle velocity” approach exemplifies this, where debate becomes a weapon to exploit liberal ideals of rationality, preventing the collective psyche from achieving the integration Jung called individuation—the process of reconciling conscious and unconscious elements to form a cohesive whole.

Bandy X. Lee’s essay, “Recovering Ourselves to Recover the World,” offers a Jungian antidote to this crisis. Lee argues that cultivating mental health is a civic responsibility, a perspective aligned with Jung’s belief that individual psychological work contributes to collective healing. She suggests practices like mindfulness, gratitude, and social connection to build resilience against authoritarian manipulation. In Jungian terms, these practices foster individuation by helping individuals confront their personal shadows—fear, anger, mistrust—and develop a stronger ego capable of resisting external coercion. Lee’s emphasis on social connection as a defense against isolation aligns with Jung’s view of the collective unconscious as a shared reservoir of human experience, where acts of kindness and trust reinforce the archetype of the Community, countering the Tyrant’s divisiveness.

Lee’s focus on happiness as a measure of collective mental health echoes Jung’s concept of the Self, the archetype of wholeness that emerges when the psyche integrates its disparate parts. By prioritizing mental hygiene—through mindfulness, exercise, or prosocial behavior—individuals can resist the “politics of misery” that Lee attributes to authoritarian leaders. This approach counters the collective shadow’s tendency toward despair, which Cottom observes in the public’s silence or self-censorship. Lee’s call for small, intentional acts of connection, such as sharing meals or volunteering, mirrors Jung’s belief that transformation begins with individual efforts that ripple outward, strengthening the collective psyche.

Cottom’s call to reject consumer-based responses, like boycotting Disney, aligns with Jung’s warning against over-identification with the persona—the social mask that conforms to external expectations. By reducing civic power to consumer choices, society risks losing its capacity for collective action, a form of psychic fragmentation that serves authoritarian ends. Instead, Cottom urges systemic change—reconfiguring courts, restoring bureaucratic legitimacy, and ensuring competitive information access—which Jung might see as a collective individuation process, where society confronts its shadow to reclaim its democratic principles.

The parallels between Cottom’s, Hartmann’s, and Lee’s critiques and Jung’s framework reveal a society at a psychological crossroads. The authoritarian consolidation of power, as seen in media monopolies, censorship, and propaganda, exploits the collective shadow to suppress dissent and fragment trust. Yet, as Lee suggests, the path to resistance lies in cultivating inner resilience and social connection, practices that align with Jung’s vision of individuation. By confronting the shadow—both personal and collective—through mental health practices and civic engagement, individuals can resist the Tyrant’s grip and rebuild a cohesive society.

Cottom’s "Mourn, or Else," amplified by Hartmann’s and Lee’s insights, paints a stark picture of a society under authoritarian threat, where the collective shadow is manipulated to erode democracy. This crisis calls for a dual approach: inward, to foster individual resilience and confront personal shadows, and outward, to rebuild trust and community. By integrating these efforts, society can move toward individuation, resisting the Tyrant’s chaos and reclaiming the archetypes of wisdom and connection that underpin a healthy democracy. The challenge is to recognize that the work of healing the self is inseparable from healing the world.