- Out of United States

- Posts

- Sublime Insight into Time & Nature

Sublime Insight into Time & Nature

The Mesoamerican Calendar and the Prophecy of Ecological Collapse

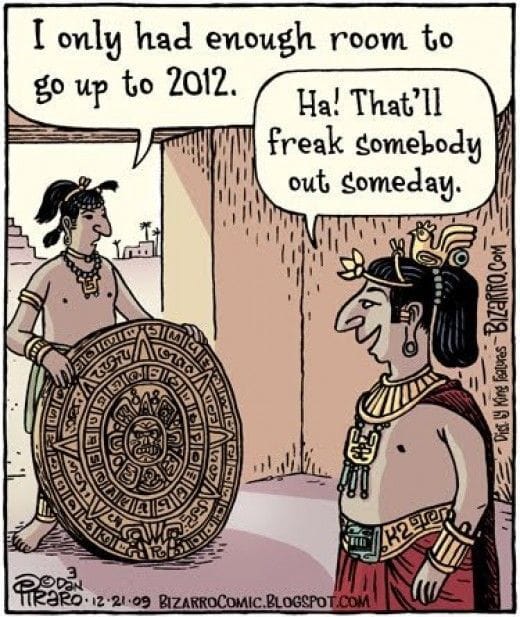

The Mesoamerican Long Count calendar, most famously associated with the Mayan civilization, has long fascinated scholars, mystics, and the general public, particularly due to its supposed "end" in December 2012. Popular narratives often framed this date as an apocalyptic prophecy, but deeper examination reveals a sophisticated cyclical understanding of time embedded in Mesoamerican cosmology.

The 2012 endpoint of the Long Count calendar, marking the conclusion of the Age of the Jaguar and the resetting of a major cycle, may have coincided with a critical threshold in Earth's ecological balance, specifically the point of no return for accelerated climate change as warned by climate scientist James Hansen in the 1980s. The creators of this calendar, potentially inheriting knowledge from an earlier culture, possessed an extraordinary insight that transcended linear time, aligning their cyclical calendar with the rhythms of nature and humanity’s impact on the planet.

The Long Count calendar is a hallmark of Mesoamerican ingenuity, particularly associated with the Classic Maya civilization (c. 250–900 CE). Unlike the Gregorian calendar, which is linear, the Long Count is a cyclical system designed to track vast expanses of time. It measures time in units such as k’in (1 day), winal (20 days), tun (360 days), k’atun (7,200 days, or roughly 20 years), and b’ak’tun (144,000 days, or roughly 394 years). The calendar’s largest commonly referenced cycle, the 13th b’ak’tun, concluded on December 21 or 23, 2012, marking the end of a 5,125-year cycle that began in 3114 BCE.

This date was not an "end" in the apocalyptic sense but rather a reset, akin to a cosmic odometer rolling over. For the Maya, time was cyclical, with each cycle associated with creation, destruction, and renewal. The Popol Vuh, the sacred text of the K’iche’ Maya, describes multiple world ages, each ending in catastrophe followed by rebirth. The 2012 date marked the transition from the Age of the Jaguar to a new cycle, symbolizing transformation rather than annihilation. This cyclical view contrasts sharply with Western linear time, suggesting a worldview attuned to natural rhythms and long-term patterns.

James Hansen and the Climate Change Threshold

In 1988, NASA scientist James Hansen delivered a landmark testimony to the U.S. Congress, warning that greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from human activities were warming the planet at an unprecedented rate. Hansen’s research highlighted that rising levels of carbon dioxide (CO₂), methane (CH₄), and other GHGs were pushing Earth toward dangerous climate tipping points. By 2012, global CO₂ concentrations had reached approximately 394 parts per million (ppm), up from 280 ppm in pre-industrial times, with emissions continuing to climb despite international efforts like the Kyoto Protocol.

The concept of Earth Overshoot Day, which marks when humanity’s demand for ecological resources exceeds the planet’s capacity to regenerate them, provides a parallel framework. By 2012, Overshoot Day had crept earlier each year, falling in August, signaling that humanity was depleting resources faster than ever. This ecological imbalance, coupled with Hansen’s warnings, suggests that 2012 may have represented a critical juncture—a point where the cumulative effects of deforestation, industrialization, and fossil fuel consumption locked in the Mesoamerican calendar's alignment with this ecological crisis.

The Maya civilization, flourishing in what is now southern Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, and Honduras, was one of the most intellectually advanced societies of the ancient world. Their achievements in astronomy, mathematics, and architecture are well-documented, with cities like Tikal, Chichén Itzá, and Palenque showcasing their sophistication. The Maya developed the Long Count calendar to track historical and mythological events over millennia, reflecting their obsession with time, cycles, and celestial phenomena. Their cosmology was deeply tied to the natural world, with gods representing maize, rain, and the sun, and rituals often centered on ensuring agricultural fertility and cosmic harmony.

The Maya believed that time was governed by divine forces, with each cycle imbued with spiritual significance. The Long Count’s starting point in 3114 BCE corresponds to no known historical event but aligns with the mythological creation of the current world age in the Popol Vuh. This suggests the calendar was not merely a chronological tool but a sacred framework for understanding humanity’s place in the cosmos. The 2012 endpoint, therefore, was not a prediction of doom but a marker of transformation, potentially reflecting an awareness of humanity’s long-term impact on the environment.

The Hypothesis: A Prophetic Insight into Climate Change

The hypothesis that the 2012 endpoint of the Long Count calendar coincided with a critical threshold for climate change is both provocative and speculative. By 2012, global GHG emissions had reached levels that, according to climate models, made it increasingly difficult to limit warming to 1.5°C or 2°C above pre-industrial levels, as outlined in later agreements like the Paris Accord. Hansen’s warnings from the 1980s about tipping points—such as melting polar ice caps, permafrost thaw, and disrupted ocean currents—were becoming reality, with 2012 marking a year of record Arctic sea ice loss and extreme weather events. Earth Overshoot Day’s steady advance underscored humanity’s unsustainable trajectory, aligning eerily with the Mesoamerican cycle’s conclusion.

Could the Maya, or their predecessors, have possessed an insight that transcended time, encoding a warning about ecological collapse into their calendar? This idea challenges modern assumptions about ancient knowledge but aligns with the Maya’s cyclical worldview. Their calendar was not a random construct but a system rooted in precise astronomical observations, including the precession of the equinoxes and Venus cycles. If the 2012 date was indeed a marker of ecological overshoot, it suggests a profound understanding of humanity’s relationship with the Earth, perhaps gained through observation of natural cycles or inherited from an earlier culture.

Human settlement in the Americas dates back to at least 15,000–20,000 years ago, with evidence of complex societies emerging much later. By 3500 BCE, agricultural practices (maize, beans, squash) were established in Mesoamerica, providing a stable food surplus. This allowed for population growth, sedentism, and cultural specialization, setting the stage for the Olmecs (c. 1200–400 BCE), based in the Gulf Coast region of modern Mexico, who developed key cultural traits—monumental architecture (e.g., colossal heads), urban planning (e.g., San Lorenzo, La Venta), writing systems, and a calendar—that influenced later Mesoamerican civilizations.

The Olmec calendar is likely the one that the Maya inherited, as they are considered the "mother culture" of Mesoamerica. Sites like La Venta and San Lorenzo reveal their advanced understanding of astronomy, with alignments of structures to celestial events. The Long Count’s earliest known inscriptions, such as those at Tres Zapotes, are Olmec in origin. The Popol Vuh’s references to previous world ages and the Maya’s belief in a primordial wisdom show their understanding of time’s cycles. This raises the possibility that the Long Count’s structure, with its 5,125-year cycle, was designed to mark a critical juncture in human history.

The Maya’s cyclical view of time contrasts with the linear progress narrative of modern industrial society, which often ignores long-term consequences. The Long Count’s 2012 endpoint could symbolize a moment when humanity’s cumulative environmental impact—deforestation, soil depletion, and GHG emissions—reached a point of no return, as Hansen’s models suggested. The Maya’s attunement to natural cycles, evident in their precise tracking of solar and lunar patterns, may have allowed them to perceive humanity’s trajectory as part of a larger cosmic rhythm. Their calendar’s reset in 2012 could reflect an understanding that unchecked exploitation of nature would lead to a transformative crisis, akin to the mythological destructions of previous world ages.

The Maya/Olmec’s sophisticated astronomy and mythology suggest a holistic worldview that integrated human activity with the Earth’s systems. For example, their rituals often addressed environmental balance, such as offerings to rain gods to ensure agricultural success. If the Long Count was designed to mark a 5,125-year cycle culminating in ecological overshoot, it implies a foresight that modern science only began to quantify in the 20th century.

The Mayan culture emphasized harmony with nature, yet their own civilization faced ecological challenges, such as deforestation and soil exhaustion, which contributed to the Classic Maya collapse of roughly 900 CE. As with 2012, the point-of-no-return on their calendar may have been 10.0.0.0.0, the end of Baktun 10 in 830CE. Baktun endings were rare and symbolically tied to cosmic cycles.

While significant, Katun endings, like 10.4.0.0.0 in 880 CE, were less monumental than Baktun endings. They were routinely marked by inscriptions, especially in thriving centers like Chichén Itzá or Uxmal, but by 880 CE, the southern lowlands of the Mayan empire were already in decline.

This parallel suggests they may have encoded lessons from their own environmental missteps into the Long Count, warning future generations of the consequences of imbalance. Tortuguero Monument 6, from a 7th-century Maya site in Tabasco, Mexico, is the only known inscription that explicitly references the 13.0.0.0.0 date (December 2012). The text, carved on a stela, commemorates the reign of ruler Bahlam Ajaw and mentions the completion of the 13th b’ak’tun.

The relevant passage reads: “At the completion of 13 b’ak’tuns, on 4 Ahau 3 K’ank’in, it will happen, the descent of Bolon Yokte’ K’uh.” Bolon Yokte’ is a deity associated with war, creation, and transitions, possibly linked to cycle endings. The inscription is damaged, and the exact nature of the “descent” is unclear. It may refer to a ceremonial event, a cosmic alignment, or a divine act of renewal, but it does not specify post-2012 events.

Scholars interpret this as a ritual marker, not a doomsday prophecy. The Maya often projected future cycle endings to legitimize current rulers, suggesting Bahlam Ajaw’s reign was cosmically significant. The lack of catastrophic imagery and the focus on a deity’s descent imply a transformative, not destructive, event.

In 2012, the world did not end, but the years since have seen escalating climate impacts—wildfires, hurricanes, and rising sea levels—consistent with Hansen’s predictions. The failure of global society to heed early warnings raises questions about whether modern civilization is entering a cataclysmic cycle. The Mesoamerican calendar’s cyclical nature offers a framework for rethinking humanity’s relationship with time and nature, urging a shift from linear exploitation to sustainable coexistence.

In his 1988 testimony to Congress, Hansen warned that greenhouse gas emissions were already driving dangerous warming. By the 2000s, he argued that CO₂ levels above 350 ppm were unsafe, a threshold crossed in 1988.

By 2012, global CO₂ concentrations were around 394 ppm, and Earth Overshoot Day had advanced to August, indicating humanity’s ecological footprint was far exceeding planetary limits. Hansen’s 2008 paper, “Target Atmospheric CO₂: Where Should Humanity Aim?” suggested that exceeding 350 ppm for an extended period would trigger irreversible ice sheet loss and sea level rise. This implies that by 2012, some long-term impacts (e.g., partial Greenland and Antarctic ice melt) were likely already locked in due to cumulative emissions and thermal inertia, which delays full warming effects by decades.

The 2010–2020 Acceleration as a Tipping Point:

Hansen’s 2025 study identifies 2010 as a pivotal year when warming began accelerating, driven by reduced sulfate aerosols from cleaner shipping fuels. This reduction unmasked the warming effect of existing greenhouse gases, equivalent to a massive increase in CO₂ forcing.

The study notes that global temperatures surged by over 50% compared to the prior four decades, with 2023 (1.5°C) and 2024 (1.6°C) exceeding expectations. January 2025 hit 1.75°C above pre-industrial levels, despite La Niña conditions, which typically cool the planet.

This acceleration suggests that by the mid-2010s, the climate system may have crossed a threshold where feedback loops (e.g., reduced albedo from ice melt, permafrost thaw) began amplifying warming beyond easy reversal. The 2020 International Maritime Organization (IMO) regulations further reduced aerosols, locking in this trend.

Connection to the Mesoamerican Calendar’s 2012 Endpoint:

The hypothesis, that the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar’s 2012 endpoint (end of the 13th b’ak’tun) marked a point of no return for ecological overshoot, aligns with Hansen’s warnings. By 2012, global CO₂ levels, deforestation, and resource depletion had reached levels consistent with Hansen’s concerns about unsafe thresholds. For example, 2012 saw record Arctic sea ice loss, a key indicator of polar amplification, which Hansen now links to AMOC risks.

When Did Irreversibility Occur?:

Based on Hansen’s 2025 findings, the period around 2010–2015 likely marks when accelerated warming became difficult to reverse, as aerosol reductions and high climate sensitivity amplified existing GHG effects.

For specific tipping points, such as AMOC collapse, Hansen suggests a window of 20–30 years (2045–2055) unless emissions are sharply cut. However, the groundwork for this risk was laid earlier, with CO₂ levels exceeding 350 ppm in 1988 and continuing to rise through 2012 (394 ppm) and 2024 (419 ppm).

Thermal inertia means that even if emissions stopped today, warming would continue for centuries due to ocean heat storage, locking in some impacts (e.g., 1–2 meters of sea level rise) by the early 2000s.

Hansen’s work suggests that the early 2010s, particularly around 2012, marked a critical juncture where accelerated warming and feedback loops (e.g., albedo reduction, ice melt) made certain impacts effectively irreversible without radical action. However, “irreversibility” varies by impact. Some effects, like multi-meter sea level rise, are locked in over centuries, while others, like AMOC collapse, remain avoidable with immediate action. Hansen’s emphasis on 2025 as an “acid test” (due to sustained high temperatures despite La Niña) suggests we are currently in a window where mitigation could still prevent the worst outcomes, but the margin is narrowing rapidly.

The Maya’s Long Count calendar, ending in 2012, may not explicitly predict climate change, but the Tortuguero Monument 6 inscription, referencing a deity’s descent in 2012, suggests a ritual transition, not a catastrophe, but could metaphorically reflect an awareness of humanity’s impact on natural cycles. The alignment of 2012 with rising CO₂ levels (394 ppm) and Hansen’s warnings about unsafe thresholds (350 ppm) supports the idea that the Maya, or their Olmec predecessors, encoded a sensitivity to environmental limits, perhaps through observation of long-term cycles, cultural memory, or transcendent insight. As humanity grapples with the consequences of overshoot, the Mesoamerican perspective offers a timeless reminder: cycles end, but renewal is possible if we act in harmony with the Earth.

Other Long Count inscriptions, such as those at Palenque, Copán, or Quiriguá, demonstrate the Maya’s ability to project dates far into the future, sometimes millions of years. Palenque’s Temple of the Inscriptions mentions a date in 4772 CE...2,747 years from now?! These inscriptions show that the Maya assumed time would continue beyond 2012, with no indication of an apocalyptic end. I think we’ll need good luck with that.